One thing I think is often misunderstood is what exactly VCs are willing to invest in.

Understanding how VCs think about markets is critical for your chances to get funding.

If you don’t understand it, you will waste a lot of time trying to raise money, when it is not going to work.

Once you understand what VCs are looking for, and the economics of their business model, you can tailor your pitch more effectively.

So let’s dive in. 📈

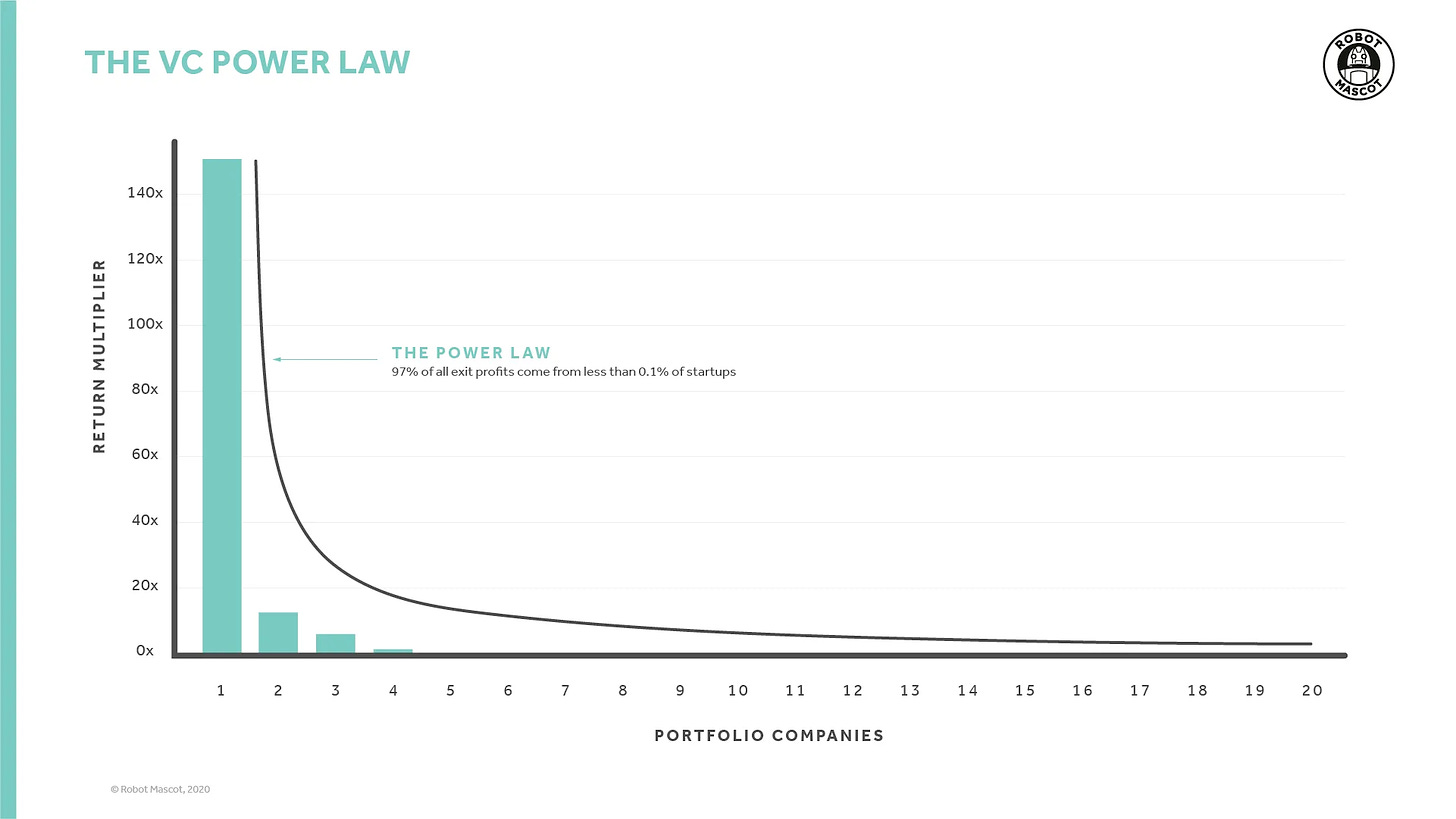

Power law distribution in VC returns

The first thing you need to understand is what the returns for a venture fund typically look like.

What you are looking at is a power law distribution in the returns on venture capital investments.

What does this mean exactly?

The most important characteristic of a power law is that a few events have very large values, and most events have nominal or small values.

This makes sense when you think about it.

Most startups fail.

A few do ok.

A tiny minority become unicorns.

This is the reality for what VC investing looks like. For example, when I was in YC in 2015, I was told that at that point something like 97% of the total returns from YC’s investments to date were from just two companies.

Can you guess which ones?

Airbnb and Dropbox.

Of course there are plenty of other YC success stories - Stripe and Coinbase come to mind - but I am sure that the power law distribution still holds true today for YC’s portfolio. The point is that most startups fail or have inconsequential outcomes.

What this means for a VC’s investment strategy

This power law dynamic for venture capital investing has a few implications.

VCs will try to invest in as many companies as feasible. Why? More bets mean more shots on goal.

Every investment needs to have at least the possibility that it could return the fund.

Let’s focus on the second point, as it’s the most relevant for you if you are fundraising.

When a VC starts a fund, it gets commitments from limited partners (LPs) – typically institutions like pension funds, endowments, or wealthy individuals – for a certain amount of money. For instance, a VC firm might raise a $100 million fund.

So when a VC is evaluation whether they want to invest in you, one thing they have in mind is whether you have the potential to "return the fund.”

This means that if you succeed, would you generate generate enough returns to cover the entire $100 million that the firm initially raised.

In this example, if the VC firm invests $10 million for a 10% stake in a startup, that startup would need to be sold or go public (IPO) at a valuation of at least $1 billion (10 times the fund size) for that investment to "return the fund."

Or lets say you are earlier, and you raised 100k from a ‘micro-VC’ that has a $10m fund. If this $100K investment is for a hypothetical 2% stake (at a $5M valuation cap), then for this investment to return the entire $10M fund, the startup would have to reach a valuation of $500M (100 times the $5M valuation cap, as 2% of $500M is $10M).

They might only get one or two winners in your entire fund, and so they absolutely have to be able to make up for all the other startups in the portfolio that won’t make it.

The bottom line is, if the upside potential is too small, there’s no point in investing, however good the business might be.

What this means for you

With this understanding of how VC’s think, we can start to think about what the implications are for you if you are trying to raise funding.

Most important, you have to be able to show that your company could be big enough one day that you could return the whole fund.

So for example, if you are approaching a $100m fund, and your total addressable market is just $10m, you are going to have a difficult time of it.

Incidentally, this is something that people in the social impact space often misunderstand. I have met many social impact founders that are interested in raising from traditional investors, but fail to appreciate that their idea is just not going to be of interest to VCs. The biggest possible size the business could get is just too small.

Taking that into account, you need to show how big an opportunity this could be for investors.

You want to make their eyes light up with the possibility.

Basically, start by thinking how you could be a $1bn company one day.

Start small, but have a path to $1bn

You might think this sounds a bit contradictory to some famous startup advice to “start small and monopolize” (Peter Thiel) or “It is better to have a small group of customers that love you than a large group that sort of like you” (Michael Seibel and Geoff Ralston).

Mark Zuckerberg and his co-founders initially launched Facebook with a focus on the Harvard University community before expanding to other universities and eventually the world.

Uber was founded with a limited number of black luxury vehicles, targeting high-end clientele. As they established their brand and gained popularity, they expanded to the mass market.

How can we reconcile this?

What you need to do is paint a picture for you investors of how you are going to get from that small group of initial enthusiasts to the massive scale you will one day reach.

You don’t have to get there all at once, and probably if you try you will fail.

If Facebook had started by targeting everyone in the world, probably it would have failed.

If Uber started by targeting every city in the world, probably it would have failed.

Tell the story of your path, how you are going to get from where you are now, to the huge company you will be in the future.

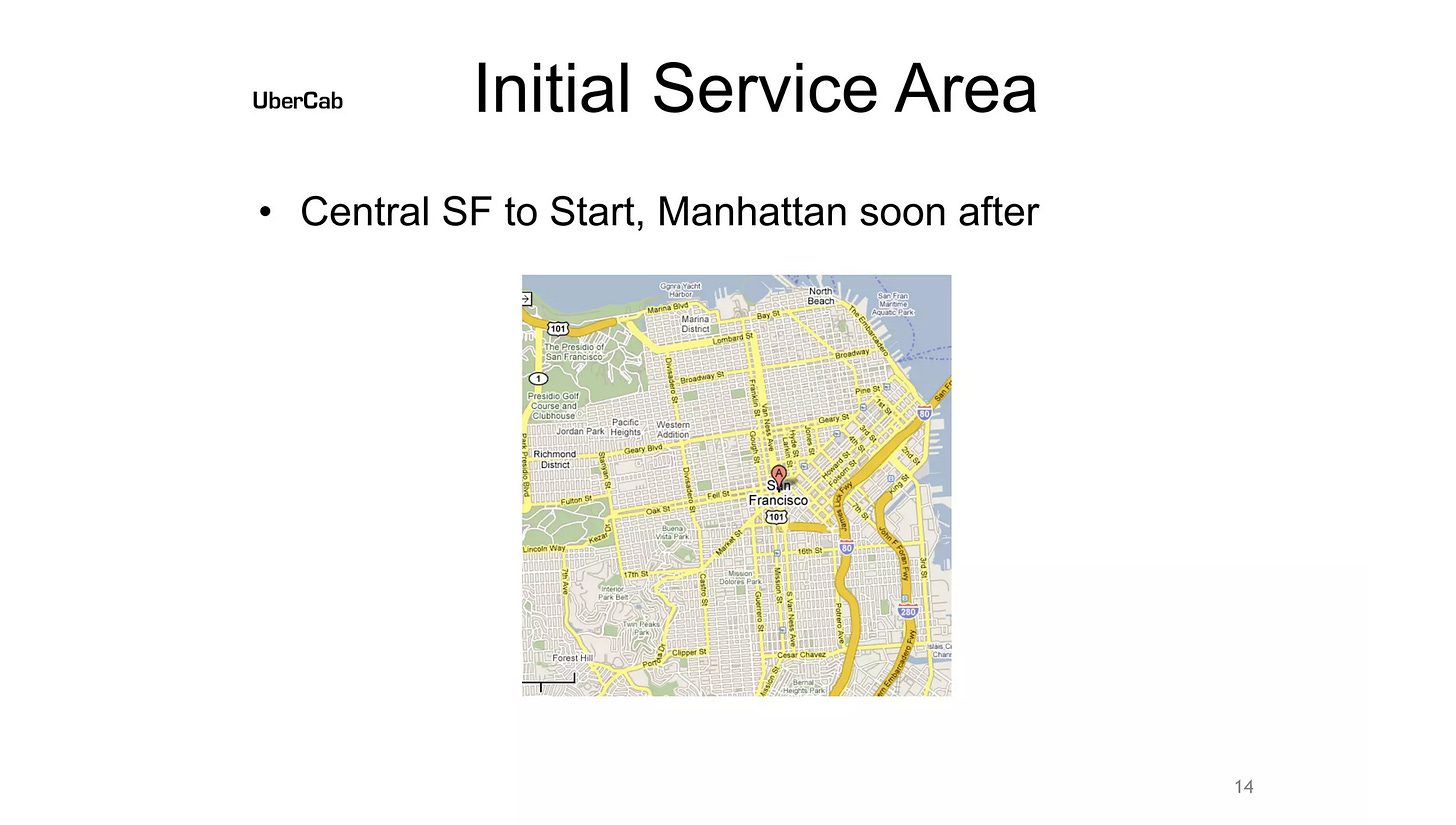

Taking Uber, you can see in their original pitch deck how they did it.

First they showed their initial market area, downtown SF.

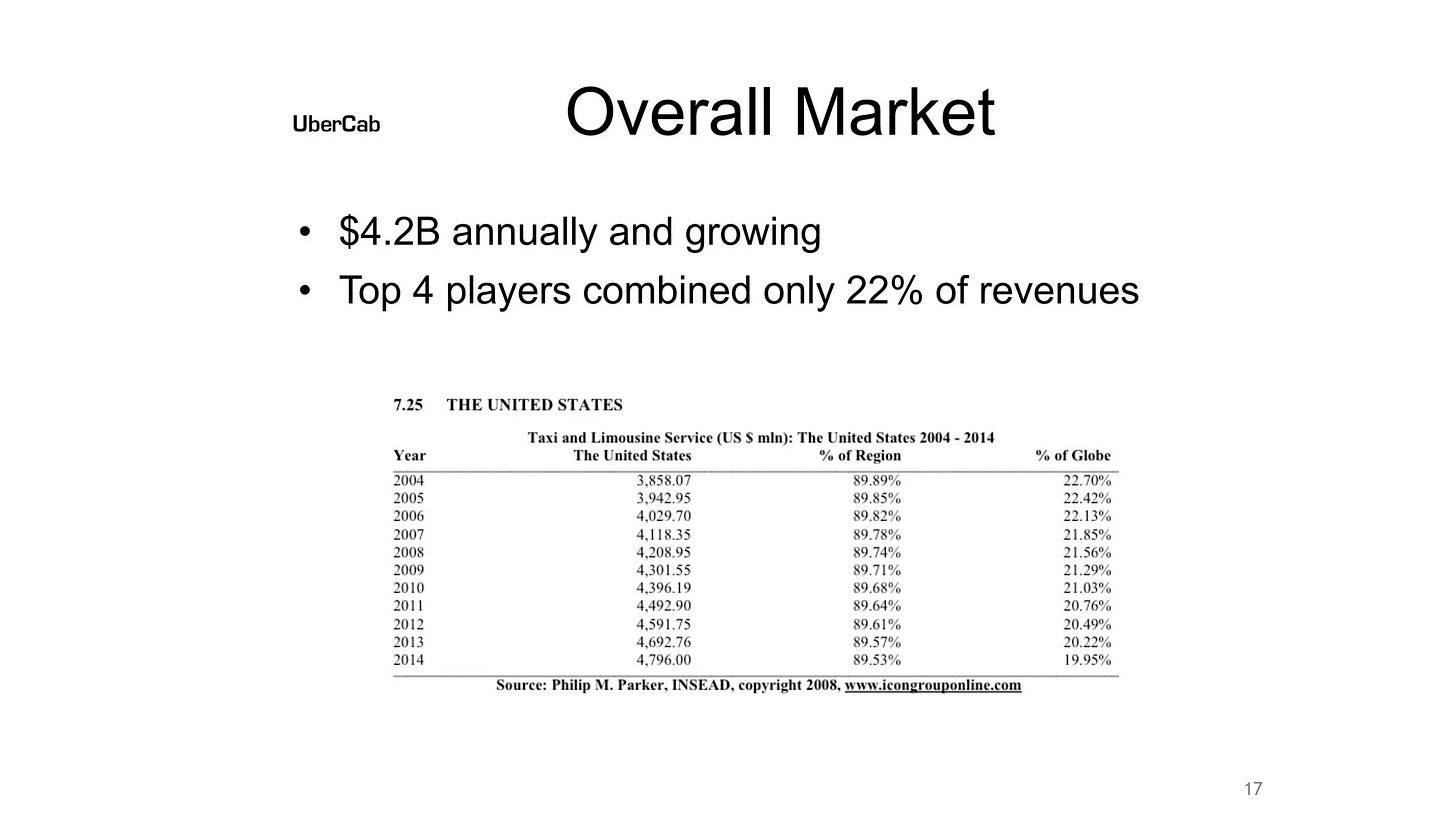

Then they showed how big was the market they would eventually be going after - the entire US taxi and limousine market. In the end, they became much bigger than even that entire market.

But the key is they showed their path SF→ USA. Their path to taking on a huge market.

The lesson here is critical for startups pitching VCs.

You have to keep the power law in mind. Remember the VC wants to know if you could one day return their entire fund.

Show how you can do this, and you will have a better chance of getting to yes.

Until next time,

Jamie

Did you enjoy this newsletter?

Please take a second to help me improve!